I am told that Grimsby is also sometimes called Great Grimsby; just not by anyone who’s been there.

It was called Great Grimsby to distinguish it from the village of Little Grimsby which lies fourteen miles to the south but the two are easy to tell apart as it is possible to visit Little Grimsby and cling on to the will to live. The church in Little Grimsby is dedicated to the saint with the second most mundane name in the great pantheon of saints: St Edith. She lived at the end of the tenth century, in fact she was only about twenty-three when she died. She was buried then dug up and re-buried but with her thumb enshrined separately. As such, she should be the patron saint of hitchhikers.

During her short life, she herself built a church dedicated to the saint with the most mundane name: St Denis, who had his head chopped off in the mid-third century and is generally depicted in paintings and statues holding his head in his hands, quite literally, as though the only portraits he ever posed for were post mortem. Why she chose dull old headless Denis when St Drogo and St Wilgefortis were available, history does not relate.

Big Grimsby had a population of 88,243 in the 2011 census and an estimated population of 88,323 in 2019. I can only assume that eighty more people were born there than died there in the intervening years as it’s not the sort of place you’d move to. In the Domesday Book it is listed as having a population of around two hundred, maybe they should have stopped there. Perhaps I just wasn’t lucky enough to see the nice bit of Grimsby on my fleeting visit but, in fairness to me, they don’t make it easy to find. I really did try to find something great to do in Great Grimsby but even the website which lists the fifteen best things to do in Grimsby can only name ten; listing five things in neighbouring Cleethorpes instead. Out of the ten things that they do list, half are related to the fishing industry. I really did try to find something nice to say about the place, though.

They didn’t give themselves the best chance with a name like that, either. You expect the place to be bleak and gloomy before you ever even glimpse it and the seemingly endless and soulless retail parks on the approach to the town do little to disabuse you of that idea. The name means village belonging to Grim, býr being a Norse word for a settlement which is why so many places in that eastern chunk of England once known as the Danelaw, where the Vikings held sway, end with the suffix “by”. Grim is the name adopted by Odin, the all-father, when he chose to walk amongst mortals. His name comes from the Proto-Germanic name Wōđanaz, meaning “leader of the possessed”; no further questions, your honour. Odin is famous for having given up one of his eyes in exchange for wisdom. Presumably this is when he moved out of Grimsby.

Still, it could be worse, you could live in Scunthorpe. The town is dominated by the steel works and an asphalt plant. Look at the place on Google Earth and you’ll see that there is a reason why this isn’t called Scunthorpe Garden City. Of course, garden cities tend to exist in the southern half of England and not up here in the rugged, workmanlike north. Just about everyone you could ask would put Scunthorpe in the north, it’s north of Sheffield and Manchester, so that seems reasonable. However, it is 183 miles to the border with Scotland at Carter Bar and also 183 miles from St Paul’s Cathedral in central London, this must be the very definition of The Midlands; it just doesn’t feel that way.

Rowland Winn, 1st Baron St Oswald lived, in the mid-1850s, at Appleby Hall. He was aware that the Romans had produced iron in the area and so searched for ironstone on his land, finding it in 1859. He leased land for mining as well as mining his own ore. It was he who championed the building of the first iron works and the railways to transport the coal in for smelting and the finished products out to the empire. It's thanks to him that the place looks the way it does today. If it is Odin who put the Grim into Grimsby, we can only speculate as to the four-letter word the 1st Baron St Oswald put into Scunthorpe.

I tried to find nice things to say about Scunthorpe, too, and really the only thing I could think of was that, if you visit the town centre, you get two hour’s free parking but I really couldn’t find two hours’ worth of things to do.

The quickest route for me to this part of the world is up the A1 as far as Newark and then cross-country past Walt’s brother, Norton Disney, to Lincoln and then up to Scunthorpe. I am fascinated by the A1 or, as I almost inevitably prefer to think of it, The Great North Road. It is our Route 66, without a song but with a much longer history.

The Turnpike Act of 1663 called the Great North Road: “the ancient highway and post-road leading from London to York and so into Scotland”. At least part of the route could have been in use up to 10,000 years ago, as evidence of a shelter by the road which dates to the Mesolithic era was found by archaeologists working near to Catterick in North Yorkshire in 2014. They were concentrating, though, on the evidence of Roman use of the route as the road here follows the Roman Dere Street which ran from York up to the Antonine Wall near Cumbernauld.

The start of the A1 in London is at Aldersgate, one of the gates in the Roman wall surrounding the city of Londinium, and it runs all the way to Waverley railway station in the centre of Edinburgh. One road connecting two capital cities.

The first regular mail service between the two capital cities started in 1635 and took three days. The formation of the General Post Office in 1660 managed, as is often the case when a large bureaucratic body takes over a service, to double the time taken. It probably didn’t matter that much as there was one day in 1745 when there was just one letter from London to Edinburgh and another when there was only one taking the return trip. In 1758 somebody with a financial interest took a grip of things when Edinburgh merchant George Chalmers re-organised the trip and got the times down to eighty-two hours northbound and eighty-five south bound. By1832, the improvement to the roads - largely the work of Thomas Telford and John Loudon McAdam - brought those times down to forty-two hours and twenty-three minutes from London to Edinburgh and forty-five hours and thirty-nine minutes in the opposite direction.

Passenger stagecoach times had been even more amazingly long-winded. The Edinburgh Courant in 1754 advertised a stagecoach leaving every other Tuesday which took ten days to do the journey in summer and twelve in winter. I find it amazing to think of not only what the journey must have been like, with lunchtime and overnight stops at coaching inns, but also the mindset that must give you with regard to travel and, indeed, to time itself. You’d have to really want to go somewhere to invest almost two weeks in getting there. Today, I regularly fly from Edinburgh to Stansted in one hour and fifteen minutes. Admittedly, Greater Anglia and Network Rail can still make the onward service to central London take forty-five hours and thirty-nine minutes but that’s no longer the average time.

There seems to have always been a nostalgia for the road. One of my favourite books about the A1 was published twenty years before it gained that name, the book by Charles Harper is called The Great North Road, see, it had my attention right from the get-go. Even in 1901 Charles Harper was nostalgic for a road that he thought would vanish as people chose to travel by train, the motor car had not yet really caught on. I find it fascinating that places he noted or made sketches of then, as he bicycled north, are still features on the road today. He mentions Kate’s Cabin at Peterborough, which he says was a coaching inn. Today the building has gone, there’s now a petrol station and a Greggs, but it’s still called Kate’s Cabin.

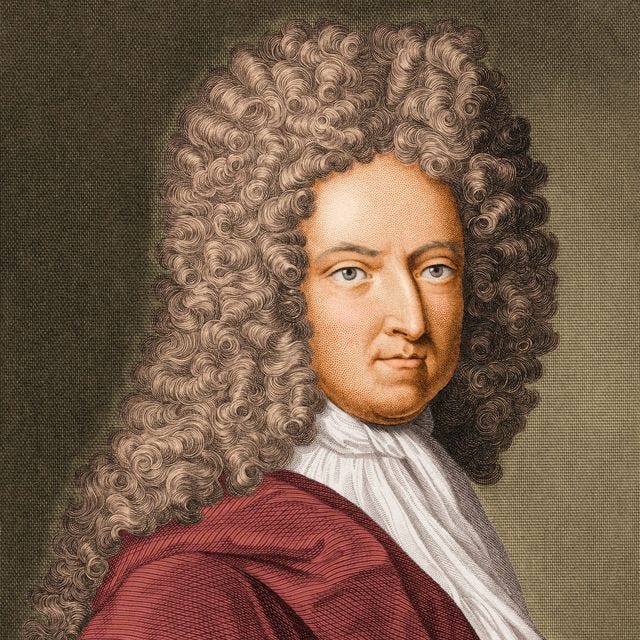

Daniel Defoe passed along what would become the A1 on his Tour Through the Whole Island of Great Britain, as one might suppose he would. He says that Stangate Hill, just north of Alconbury in Cambridgeshire where the A1 follows the route of the Roman Ermine Street, was “famous for being the most noted robbing-place in all this part of the country”. It must have held that reputation for a long time because Shakespeare’s friend, the playwright Ben Johnson, who was the spitting image of Tom Baker and just as colourful a character, walked from Bishopgate in London to Edinburgh in the summer of 1618 and was, while in an ale-house in Stukeley, warned about the area known as Stangate-in-the-Hole.

Today the B1043 parallels the modern dual carriageway, this would have been the route of the Great North Road that Defoe and Johnson knew.

We talk today of roads bypassing towns, and that’s what most of the A1 now does, but that is precisely what roads were not meant to do in the days of the stagecoach, they were there to link towns with a series of inns and public houses along the way providing rest and refreshment for travellers and horses alike at each stage. One of the few pubs outside of the towns and cities on the route which survives is The Ram Jam Inn just north of Stamford. It is reputed to get its name from a trick that Dick Turpin played on the landlady whilst he was staying here, just before he scarpered without paying the bill. So, like King Arthur and Prince Albert, Dick Turpin follows us round the country pretty much wherever we go.

In 1878, Hugh Lowther, 5th Earl of Lonsdale ran the one hundred miles to The Ram Jam Inn from Knightsbridge Barracks in London for a wager. He covered the distance in just eighteen hours, the same time it reputedly took Dick Turpin to ride from London to York just before his capture in 1735. Whilst the Ram Jam Inn still survives at the time of writing, it’s been closed for several years and is fairly derelict with permission having been given for its demolition, which is a huge shame.

The first coaching inn on the Great North Road was The Angel, Islington, well known from the board game Monopoly. By the time that you reached The Angel, you had left London far behind. Morgan’s Map of the Whole of London, produced in 1682, shows the built-up part of London ending at the Pret A Manger on the corner of Old Street and Goswell Road.

In the early nineteenth century there was a hatter’s shop here (not a milliner’s, not as posh as St Annes-on-Sea) which had a sign saying “Old Hats Beavered”, that is of no consequence at all but I can’t find out a thing like that and not let you know that, once upon a time, on the corner of Old Street and Goswell Road, rather than getting an avocado and chipotle wrap, you could have your old hat beavered.

If I want to see the England that I didn’t know as a child in Lancashire, then the A1 is where I could find it, from the centre of our capital city, through leafy Hertfordshire and Bedfordshire as well as thirteen other counties before reaching the Scottish Borders. Just after bending west to head to Edinburgh, the road passes the tiny Scottish village of Phantassie.

In my mind most of the towns and villages along the A1 will always be a fantasy. I’ll never really know what it’s like to live in them or, in many cases, even visit them. When I say that I love the A1, it is mainly the fantasy of it, the history of it, the A1 that exists solely in my mind, that I love. I do love it, though. The only thing that might improve the A1 is if they stopped writing “The North” on the road signs and, instead, wrote “T’North”; I’d like that.

So, for me, the trip is like life itself, it isn’t so much about where I start out or the destination I reach as it is about how much I enjoy the journey and the stories I encounter or tell myself along the way.