Edinburgh gives good silhouette. Churches, castle ramparts, follies, domes, towers, statues, memorials, flagpoles, cupolas, obelisks, gothic university buildings and Victorian monuments stick up into the air everywhere you look.

At sunrise or sunset you can just point your camera in any direction and press the button and you’re guaranteed something pretty. When H.V. Morton visited the city In Search of Scotland, he saw Edinburgh on a misty morning and, as the shapes emerged from the fog, he said it was like a great Armada becalmed in a grey sea. If I’d thought of that phrase, I’d probably have used it, too, even if the idea of mist-shrouded masts and sails does little to prepare you for the stunning, soaring skyline that Edinburgh has in store. It is no surprise, even if it is something of a shame, that this city inspired Hogwarts. I say it’s a shame for two main reasons.

While the idea for Harry Potter’s adventures may have arrived fully formed in J.K. Rowling’s mind on a delayed train between Manchester and London, the setting for his exploits are clearly Caledonian. JoRo notoriously sat in Edinburgh cafes writing some of the first drafts of her celebrated books and the skyline of the city clearly seeped into the pages. The most well-known of the cafes she frequented is The Elephant House and it has also played host to Ian Rankin and Alexander McCall-Smith but not to me.

The Elephant House

I stumbled, quite by accident, across The Elephant House whilst trying to find my way to Greyfriar’s kirkyard. Of course, like just about everybody, I’d heard the story of single-mum Joanne Rowling sitting in cafes writing the Potter books but, unlike the entire population of Japan, had not thought to seek out any of these establishments. Hordes of Japanese tourists taking selfies on the very latest iPhones mean that you don’t need to search very hard for The Elephant House, it is quite, quite obvious. The establishment then announces itself as the birthplace of Harry Potter with a sign in the front window. Underneath this, in Chinese, according to Google Translate, it also states that it is the Magic Coffee Museum but I fear something may have been lost in the translation.

I thought that it might be a fun idea to have a coffee and sit writing notes for this book in the place where some esteemed authors had sat. Of course, as this had never occurred to me before, not even when I knew that I was going to Edinburgh, I assumed that I was the first person to think of this. From the throngs of East Asian visitors both outside and in, it appears that I was not.

I just managed to squeeze into the front door to join the queue which then took several months to take one pace forwards. I know that elephants are reputed to have a good memory but even the sharpest would have forgotten their order before they got to the front of the queue in The Elephant House. At least I assume they would, as I never made it to the front, I gave up after the first decade or so had passed. If Joanne had had to queue like this then Harry would still be in kindergarten. I couldn’t stay any longer as I wanted to find Greyfriar’s kirkyard and I didn’t want to find it after dark.

So, that’s the first reason I think it’s a shame that she wrote the early books in Edinburgh: I can’t have a coffee where Ian Rankin had a coffee. Not a big thing, I know, but it would have been nice.

The second reason is a lot less self-centred. Quite simply, Edinburgh did not need her help, it had enough already. It had Rabbie Burns and John Knox and Adam Smith; it had a castle and tartan and bagpipes and shortbread and ghost tours; it had Robert Louis Stevenson and Walter Scott and Irvine Welsh and Muriel Spark; I mean, come on, it had Rebus, godammit. In short, it already had plenty going for it, enough to draw the tourists in, it didn’t need J.K.’s help; it was doing fine.

I mean, well done for all the books and the films and the billions of pounds you made and for defining a generation and all that but minus several million points for choosing Edinburgh. You could have had the foresight and decency to write a few pages in a nightclub in Coventry or a restaurant in Hartlepool; places which could do with a boost and didn’t already have Greyfriars Bobby.

Greyfriars Bobby

The story of Greyfriars Bobby is one of my earliest memories of Edinburgh. My Auntie Enid and Uncle George and all of my cousins lived in the area and, following my dad’s death when I was seven, my Mum and I spent some time staying with them. My Mum took me to Holyrood House and Edinburgh Castle, where, she told me, my father had been stationed at the very start of the war.

The day in Edinburgh that I remember best, though, was when my cousin, Audrey, took me to a restaurant. This episode stuck in my mind, as going to restaurants was not a thing we did a lot of when I was a child. A trip to the Little Chef off the A580 at Astley for chicken Kiev and a Jubilee Pancake was high living as far as we were concerned. When we came out of the restaurant in Edinburgh I remember seeing the little statue of the Skye Terrier, Bobby and being told the tale of how he became famous.

Bobby’s master had been a night-watchman called John Gray, who worked for Edinburgh Police. He and his little dog were inseparable until Gray’s death of tuberculosis in 1858.

It is reputed that the dog lived for another fourteen years and spent the rest of his life sat on John Gray’s grave in Greyfriar’s kirkyard. Eventually a shelter was built for Bobby, people fed him and the Lord Provost of Edinburgh paid for his dog licence; meaning that Bobby belonged to the city.

He never spent a night away from John Gray’s grave until his own death in 1872 which must have made him quite an old dog. However, it is rumoured that Bobby died and, due to his fame and popularity, was replaced with a lookalike, in the same way they say Paul McCartney was but with more Pedigree Chum and less Mull of Kintyre.

I love dogs. The last birthday present I’d been given by my dad was a dog and we were inseparable. I’ve always been soppy about dogs, I can’t watch Turner and Hooch or Marley and Me. I cried at the Scooby Doo movie when Scooby thought Shaggy wasn’t his best friend anymore. The story of Greyfriars Bobby still brings a tear to my eye today; even if I do have a sneaking suspicion that the reason he wouldn’t leave is that John Gray still had hold of his lead.

I went back to see the statue of Bobby which stands outside Greyfriars Bobby's Bar in Candlemaker Row. I patted him on the nose as thousands of others have done over the years meaning that it now glows golden against the browned bronze of the rest of the statue.

I also visited John Gray’s grave in the kirkyard which says, simply: “JOHN GRAY, DIED 1858, AULD JOCK, MASTER OF GREYFRIARS BOBBY”. This means that, either, this gravestone is not contemporary with his burial or he was not famous for much else. In truth, it does say, below these words, that the stone was erected by “AMERICAN LOVERS OF BOBBY”, and it is clearly quite new. It’s amazing to me, though, that Auld Jock would have been completely forgotten and even the letters on his grave may have weathered away, were it not for Bobby. How many lives pass and fade from memory because they had no Bobby?

From the kirk it’s just a five-minute walk past the soft brown six-storey eighteenth and nineteenth century buildings which make up the Grassmarket and its surrounding curve of streets, to the Royal Mile.

Daniel Defoe visited the area in the 1720s and saw the market – one of fifteen in the city – in operation. Of the streets nearby he said they were: "full of wholesale traders, and those very considerable dealers in iron, pitch, tar, oil, hemp, flax, linseed, painters' colours, dyers, drugs and woods, and such like heavy goods”. If he could have travelled through time to see it today, he may have been surprised to find a joke shop and The Cambridge Satchel Company along with a boulangerie and a restaurant called Maison Bleue.

Not All French

It’s not all French, though, with plenty of shops specialising in tweed and at least one kiltmaker. I bet that you can still buy drugs here, too. Edinburgh very much gives the impression that this is a possibility. Even with the boulangerie you’d never really doubt where you were, though, as on the corner of Castlehill there appears to be a perennial piper and on the approach to the castle is The Scotch Whisky Experience, hopefully nothing like my scotch whisky experience when I won a bottle at the Blackpool airshow at the age of fourteen.

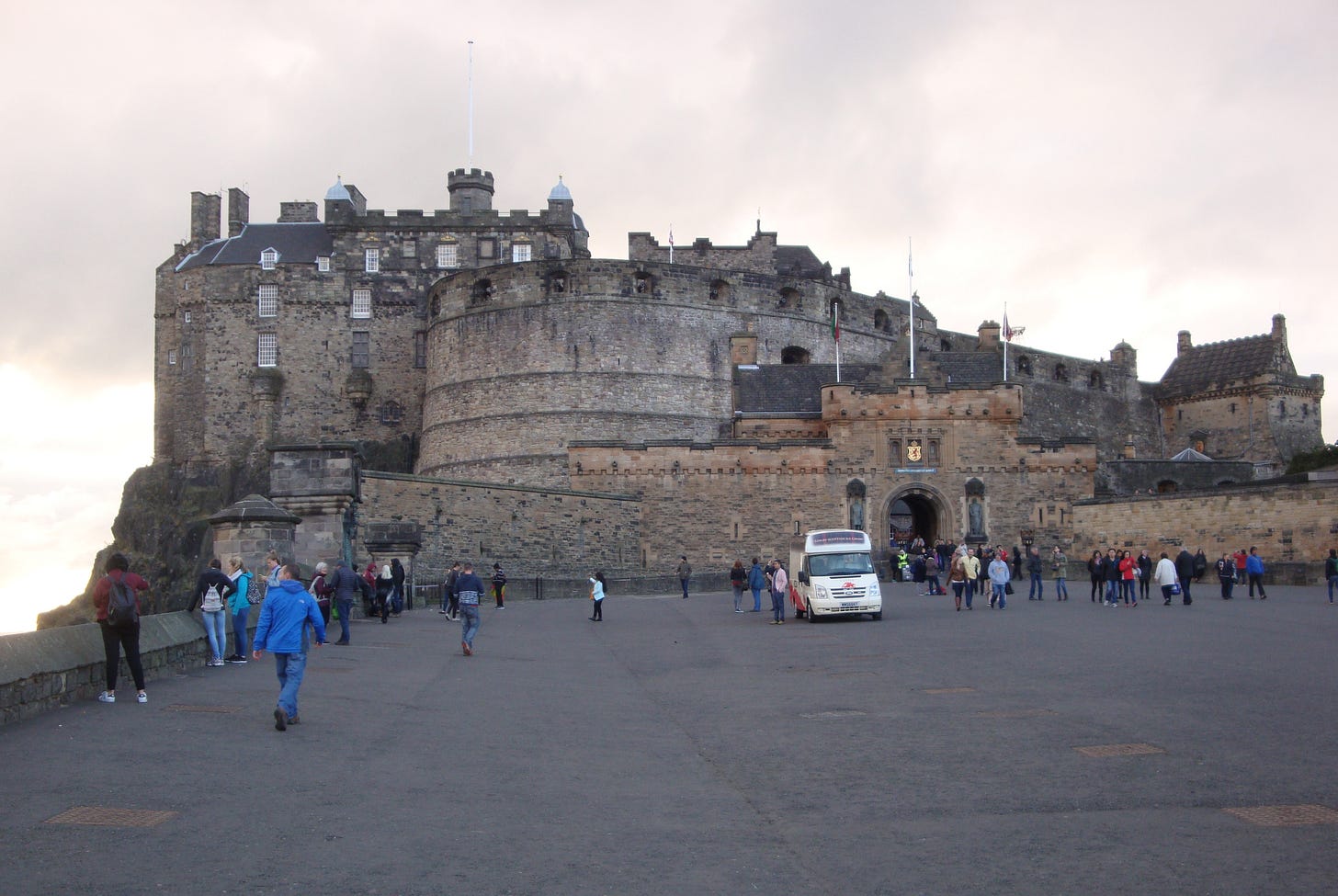

As I said, I first visited the castle as a young boy but have very few memories of it. I’m unlikely to become reacquainted with it now as it’s £18.50 to get in and so, as occupation of the huge volcanic Castle Rock can only be traced back to the second century AD, it does not quite pass the Herculaneum Test.

The Herculaneum Test

I use a method that I call the Herculaneum Test to decide whether I want to visit a tourist attraction. A ticket to visit Herculaneum, the ancient city south of Naples, is fourteen euros and that gets you access to 2,700 years of history across the entire city which was home to almost 5,000 people before it was destroyed by the eruption of Vesuvius in 79AD. It is open from 10am until 6:30pm. That’s what I want from a tourist attraction: that’s less than half a penny for every year of the site’s history or, to look at it another way, two and a half pence per minute that it’s open to me. Those prices I’ll pay.

Castle Rock is the remains of a volcanic pipe – a violent eruption from deep in the earth – which cut through the surrounding rock 350 million years ago before cooling to form a volcanic plug in the earth. Subsequent erosion has not affected the cooled magma leaving it standing 250 feet proud of the surrounding landscape, making it an easily defended location for the castle of Dauíd mac Maíl Choluim – Prince of the Cumbrians and King of the Scots.

The Esplanade in front of the castle, so H.V. Morton tells us, is part of Canada. He states that it was declared to be part of the territory of Nova Scotia in the reign of Charles I and, apparently, still was when he visited almost a century before me. I couldn’t find any evidence to suggest that had changed in the intervening years. So, perhaps I stood for a while legally on the opposite side of the Atlantic and watched the sun dip behind the battlements.

During the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, this is where those accused of being witches – more than 300 of them – were put to death. Today’s castle dominates the city and is very impressive whatever angle you see it from.

Next week, for my paid subscribers, we’ll see some more of the sights of Edinburgh. For everyone else, I’ll be back in two weeks and we can bunk off together to London’s Docklands.

Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work or read more right now here Above the Law

I miss jubilee pancakes :(