Before I start today, I just wanted to let you all know that there’s 20% off the annual subscription if you sign up during April 2024. That’s access to all posts and the complete archive.

I’ve made this post free to everyone, just so you can see what you might be missing if you don’t do the smart thing and sign up as a paid subscriber today.

One more change, from here on in I will be posting on a Friday afternoon so you have the whole of the weekend to come bunking off around the British Isles with me. What’s more, you don’t even have to read my post for yourself, I’ll even read the paid ones for you. Click on the voiceover above and you won’t need to tire your eyes. Sit back, relax and journey with me.

Following on from last week’s post about Jesus Christ, Pooh Bear and Sheffield Wednesday, let’s pop back to Cambridge.

The bit we generally think of as Cambridge, the colleges and the river and so on, actually forms a really small part of the city.

The wonders of the centre are surrounded by ordinary houses and flats and kebab shops and mini-markets. The life of most of the people in most of Cambridge most of the time is not like Brideshead Revisited, it’s just like life. That’s the problem with musing about alternative lives, we see the interesting and exciting parts and miss the mass of the everyday that surrounds every life. Perhaps I’m not cut out for such philosophical musings.

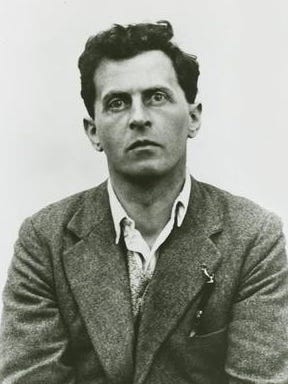

Philosophical musings are what a couple of former Cambridge residents were best known for. Ludwig Wittgenstein turned up, entirely unannounced, at the door of Bertrand Russell in Trinity College on 18th October 1911 to tell him that he wished to study philosophy under him. Apparently that was the way things worked back then. He did study at Cambridge and went on to teach here between 1929 and 1947. It is his earlier education that I found most interesting, though. Ludwig came from a very wealthy family and was schooled at home until he was fourteen. Most probably because he had no formal schooling, he couldn’t then pass the entrance exam for the Gymnasium in Wiener Neustadt and, instead, went to the smaller and less academically focussed Realschule in Linz. Here there were just three hundred pupils and one of them was just six days older than Wittgenstein; his name was Adolf Hitler. Although, despite being born in the same week in April 1889, they would have been two years apart in the school as Wittgenstein was a bit of a smartarse and was bumped up a year, whereas young Adolf was a bit of a thickie and got held back.

We know what Hitler went on to do and, despite being responsible for the VW Beetle, it is generally accepted that he was not universally liked. Ludwig was rather more respected and had a long career as a philosopher.

Wittgenstein focussed initially on logic and most authors would now go off and find out exactly what the study of logic entailed and then tell you about it as though they had known all along. I, on the other hand, will tell you a joke.

There are these two blokes stood in their local pub, having a drink and a chat when this rather foppish and curious looking fella walks in.

“Who do you reckon that is?” Mick asks.

“Not the faintest.” Pete admits.

“I’ll go and ask,” Mick tells him and heads off across the pub. “Excuse me sir,” he says when he reaches the gentleman, “I’ve not seen you in here before and me and my friend were wondering who a gentleman such as yourself might be.”

“M..M…My name,” the gentleman tells him, “is L…L...Ludwig Wittgenstein and I am Professor of Logic at the University of C…C…Cambridge.”

“Thank you, sir,” says Mick, touching the peak of his cap.

“Tell me, do you know what logic is?” asks Wittgenstein.

“No sir, no I don’t.” Mick confesses.

“Then please allow me to explain by way of an example. Do you keep fish?”

“I do sir.”

“And do you keep them outside?”

“Indeed I do,” Mick confirms.

“Well,” says Wittgenstein with a trace of an Austrian accent, “if you keep fish and you keep them outside then you must have a big house and if you have a big house you probably have a f…f…fine motor car.”

“Correct on both counts.” Mick nods.

“Well, if you keep fish outside and have a big garden and a big house and a f…f…fine motor car then you must have plenty of money and I deduce that you will have a beautiful wife.”

“Very beautiful, sir.” Mick smiles and sips his beer.

“Therefore, I would v…v…venture to suggest that you are satisfied matrimonially and do not masturbate very often.”

“Well I never,” Mick gasps, “you’re right on all counts there, sir.”

“And that,” Wittgenstein tells him, “is logic. From asking a question about fish, I can surmise that you do not masturbate very often.”

“Incredible sir, truly incredible, thank you.” Mick heads back to Pete.

“Who was that then?” Pete asks.

“That there is Professor Ludwig Wittgenstein, Professor of Logic at the University of Cambridge.”

“I see,” Pete says.

“Tell me, do you know what logic is?” Mick asks.

“I don’t, Mick, no”

“Then please allow me to explain by way of an example. Do you keep fish?”

“No Mick, never have.”

“Well, Pete, you’re a wanker.”

That may not be exactly as it happened and might not be precisely what Wittgenstein had in mind when he taught logic but he probably never got a laugh.

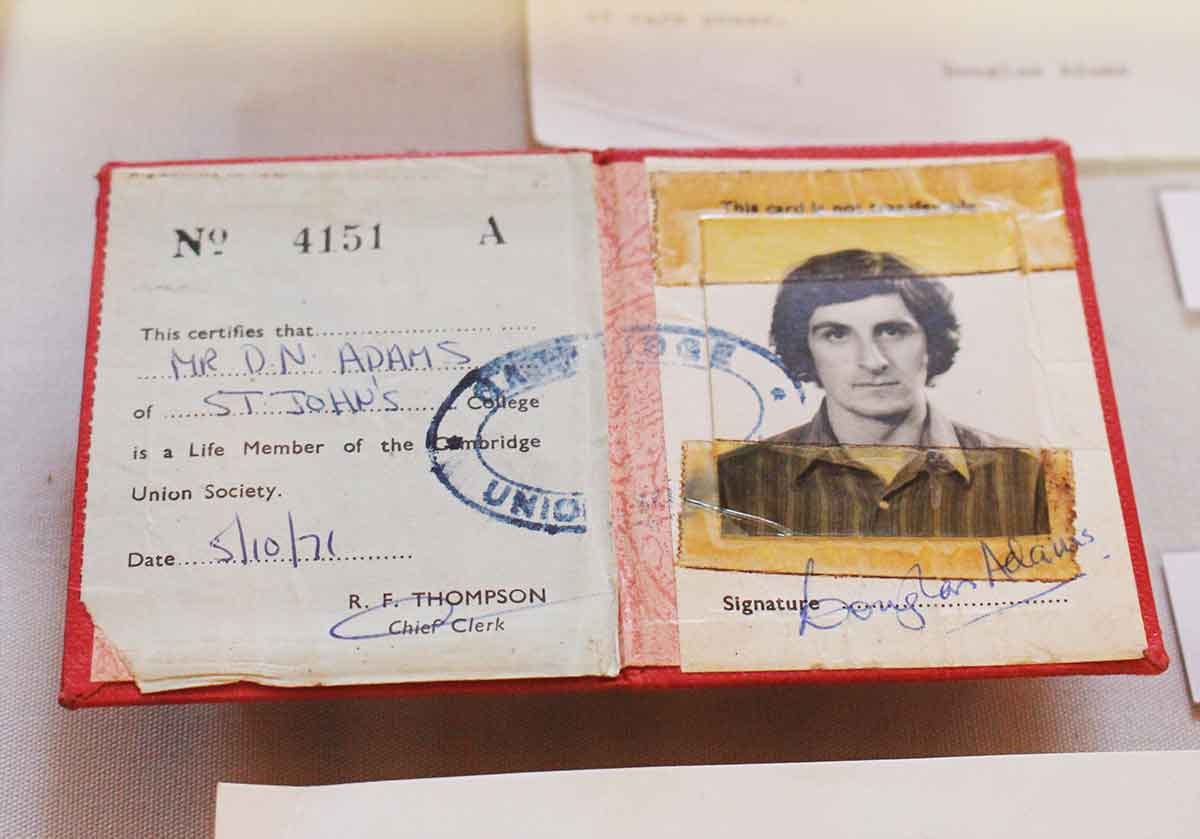

Someone who definitely did get a laugh knew this city well and has long been a literary hero of mine. Cambridge was the place of his birth and his university education. His name was Douglas Noel Adams. He was born here in the early spring of 1952 but grew up in Brentwood in Essex, returning in 1971 to study at St John’s College.

After university, as well as being a bodyguard, a chicken shed cleaner, a hospital porter and a builder of barns, he did a bit of writing. He wrote for the Monty Python team but this is not the reason I loved his writing. He wrote scripts for Doctor Who but this, even though they were for episodes featuring Tom Baker, is not the reason that I love his writing.

The reason I love his writing is that, when I was ten, he published a novel based on a radio series he had written. That novel was The Hitchhikers’ Guide to the Galaxy. I didn’t really become aware of it until a couple of years later following the TV series based on the book based on the radio series. I was, as we know, largely raised by the television and this was not like any television I had watched before. The television series led me to the book and the book and its sequels, kept me company throughout my teenage years.

There were points in my early teens which were not always the happiest of times. My mum was living with a man who would regularly beat her and I’d lie awake listening to her plead for him to stop, listening to the blows land, listening to her hit the walls or the floor, listening to her screams and to his rage. No matter who you are, no matter how cheerful and optimistic your natural personality, no matter how good your friends are, this will make your life sad.

When I was twelve or thirteen, this was my life. He would disappear for weeks on end but that was no respite as I knew he’d be back. When he was back, everything was tense, waiting for the next time he’d explode. It was generally quite late in the day when he did and I was generally in bed. I dreamed of stopping him, I dreamed of sticking a knife in his side and twisting it and watching him slowly and painfully die. I dreamed of keeping him tied up in a cellar and occasionally visiting to beat him with a baseball bat until he eventually died in agony. I never did, of course, and I also never understood why my mum let it go on. She was not a weak and feeble woman, she had friends whose husbands offered to give him a taste of what he handed out. She never made it stop, though.

During this time, while contemplating suicide as the only way out, I would go to the beach with my dog and sit and read The Hitchhikers’ Guide to the Galaxy and be transported away from it all for a while to distant parts of the universe. The book made me laugh, it made me think, it made me aware of different possibilities, it let me know that the whole world was not like mine, it gave me hope. That’s what you need when you’re trying to decide whether to see tomorrow, hope that it could be different. That’s how much his books meant to me.

Adams said that, when he was a teenager, the Beatles and then Monty Python were “messages out of the void saying there are people out there who know what it’s like to be you”. That’s what he passed on to me. He later noted that he started writing the book “from a place of utter misery” and that he wrote himself “back up out of that”. Apparently a lot of people told him that they’d been depressed or upset when they started reading the book but that it had helped them through difficult times. I wasn’t alone and somehow his book showed me that and lifted me up.

So, now I sit in the café just opposite Douglas Adams’ old college and think about his life and the books he wrote. His tales of Arthur Dent and Dirk Gently took me through my teens. I was not allowed to do O Level English as I failed the exam at the end of my third year in high school. I failed it because, when asked to write a review of a book, I wrote out, word for word, from memory, the introduction and first chapter of The Hitchhikers’ Guide to the Galaxy. I had to do CSE English and spend two years with teachers telling me I was too good to be doing CSE English, as though that was something I had chosen to do.

When I was in my twenties I read the fifth book in the poorly named Hitchhikers’ trilogy, Mostly Harmless and I still loved his writing. Today I have The Long Dark Teatime of the Soul on audiobook on my phone, I listened to it today as I drove to Cambridge and I’m listening to it now. I still love his use of language and his fantastic, inventive mind. I know some of his characters, people who never lived except in the mind of a fellow ape-descended lifeform, better than I know some friends. Douglas Adams died at the age of just forty-nine in 2001 but his thoughts are still alive in my head now. That is the incredible thing that writing can do, it can make your thoughts immortal. Well, that and saving twelve-year-olds from suicide.

Let me know what you think of the changes by leaving a comment such as “For God’s sake shut up” or “Please, no more”.

Love love love this recording! And the piece over all. Books are, indeed, powerful.

I'm a bit behind on catching up with my Bunking Off - but I glad I didn't skip a single installment.

This one might be your best so far - a wonderful roller coaster from a wanker joke to a very real and serious story from your past which I'm sure remains a very present part of who you are today.

I still find myself, when given what I see as a fairly menial task, lamenting out loud what a waste it is when I have "... a brain the size of a planet... " and the Douglas Adams fans always give themselves away when they hear it.