A long post but, hey, it’s a Bank Holiday, you’ve got time to read it.

There are many things, people and places in life that might catch your eye but only a very few that capture your heart. One of the locations that has had a place in my heart since my very first visit on 26th May 1986 is the Imperial War Museum at Duxford.

At the time, I was a seventeen-year-old air cadet with aspirations to fly, having only a month before soloed a glider for the very first time. That my future would be as aircrew in the Royal Air Force I had no doubt. I believed that with the certainty that can flourish only in youth, and which age too often cuts back.

I’d read a great deal about the RAF and some of the exploits of its most famous flyers. Few, if any, have achieved the fame of one man whose life and character fascinated me. It was someone who had flown from here at an important time in Duxford’s history. It’s also someone in whose life Duxford played a big part.

Perhaps it’s a story you’ve heard before, it may even be one that you know well and it’s only one of thousands of stories of the people who were based at Duxford between its opening as a Royal Flying Corps Mobilisation Station in March 1918 and its closure as an RAF jet fighter base in October 1961.

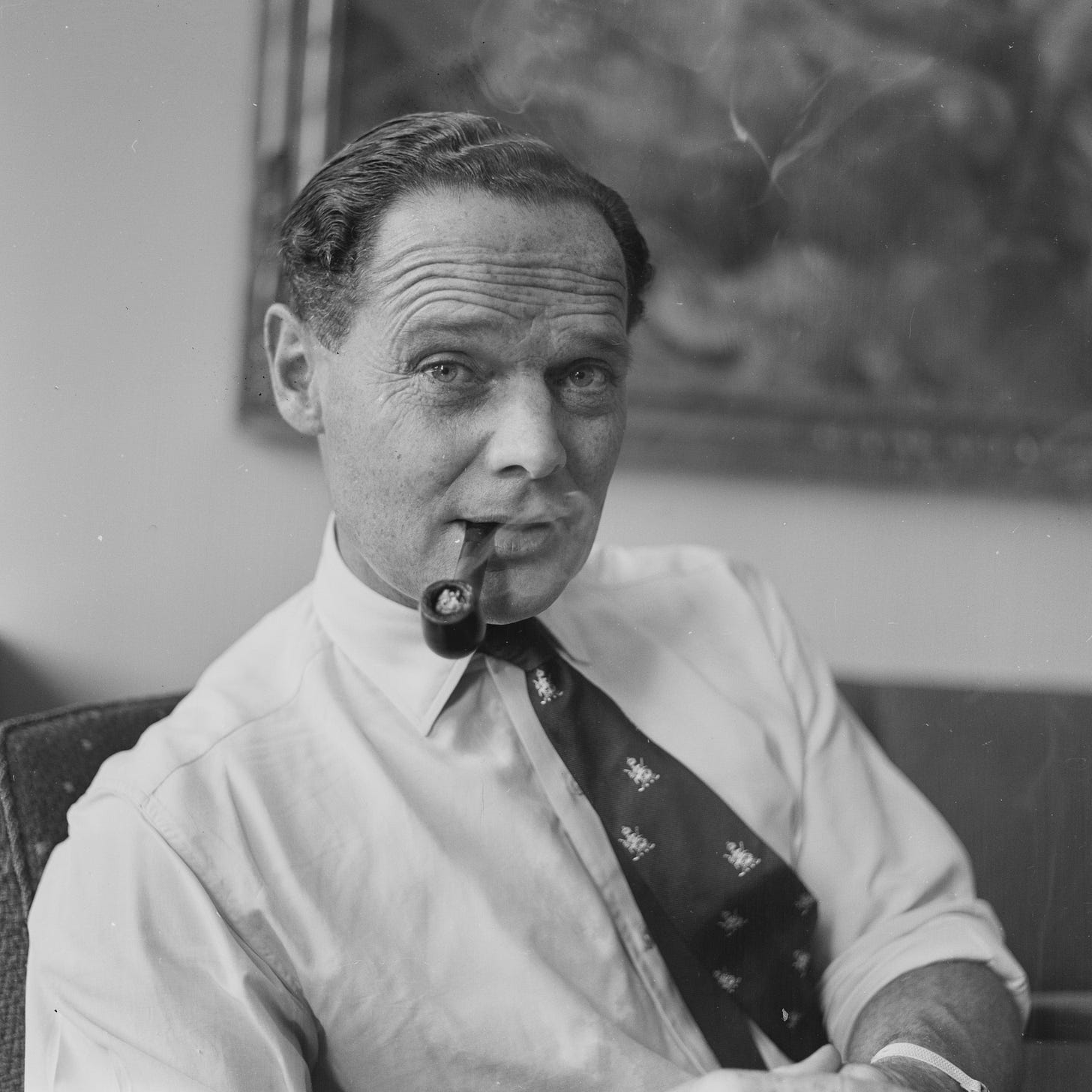

The person I’d like to talk about is Douglas Robert Steuart Bader.

He was born in St John’s Wood in north-west London, home of Lord’s Cricket Ground, on 21st February 1910, the second son of Frederick and Jessie Bader. Frederick was a civil engineer who worked in India and by the time that Douglas was just a few weeks old his father, mother and older brother, Derick, had returned to the subcontinent.

Deemed too young to join them Douglas was sent to stay with relatives, the McCann family, who lived near Ramsey on the Isle of Man. He was two years old before he went out to India to join the rest of the family.

When he was five his father went off to war, returning only infrequently over the next seven years and dying from wounds when Douglas was twelve. The early loss of a father has a huge impact on young boys and their developing character.

Famous Alumni

By this time Douglas was already showing real promise as a sportsman and was captain of the rugby and cricket teams at St Edward’s School, Oxford. As an aside, other school alumni included Sir Geoffrey de Havilland, the designer and builder of so many wonderful aircraft, and Guy Penrose Gibson VC, leader of 617 Squadron on the famous dams raids.

Douglas was allegedly once given a beating by an older boy for bowling him out in a house cricket match – the older boy was Laurence Olivier the actor who went on to play Air Chief Marshal Sir Hugh Dowding in the film, The Battle of Britain, filmed in large part at Duxford.

It was actually the chance to play sport which first attracted Douglas to the Royal Air Force College at Cranwell. In 1927 he wrote to his uncle to ask for advice and, perhaps, a little help to get in. His uncle, Cyril Burge, was well placed to assist, having been a Royal Flying Corps pilot in the Great War, adjutant of the RAF College and personal assistant to the Chief of the Air Staff, Sir Hugh Trenchard.

Bader managed, after a good deal of swotting, to score 235 out of 250 on the entrance exam which won him a scholarship. He spent two years at Cranwell – which was in those days was rather like a university taking boys from public schools and turning them into future senior officers.

Royal Air Force

He loved his time there, still playing cricket and rugby and adding hockey and boxing to the list of sports at which he excelled. Of course, he also learned to fly, going solo in Avro 504 J8534 on 12th February 1929.

On 26th July 1930 Pilot Officer Bader graduated from Cranwell with a final report which read, simply and concisely, “Plucky, capable, headstrong”.

He was posted – along with his good friend Geoffrey Stephenson - to 23 Squadron at RAF Kenley, flying the Gloster Gamecock. He arrived on 25th August 1930. The squadron was commanded by Sqn Ldr Henry Woollett, a Great War fighter ace, having scored six victories in just one day flying a Sopwith Camel with 43 Sqn on 12th April 1918.

Always keen to be one of the best and to show off just a little, Douglas set his sights on being one of the select few who were chosen to fly aerobatics at the annual Hendon air display. In the summer of 1931, luck was on his side as he happened to be part of the last flight in the air force to fly the Gamecock; the rest of the RAF, including the other flights in 23 Squadron, having re-equipped with the Bristol Bulldog in the spring.

Douglas was chosen to fly as the wingman to flight commander Harry Day at the Gamecock’s final display at Hendon in June 1931 in front of 175,000 people – a truly amazing number, even the airshow weekends at Duxford can only attract around 40,000 people. The Times described their display as “the most impressive air exhibition ever witnessed in England”.

Soon after, they too re-equipped with the faster but less agile Bristol Bulldog. On 14th December that year Bader tagged along with a fellow pilot Geoffrey Phillips who was flying to the civilian Woodley Aerodrome to have lunch with his brother who ran the aero club there. They were joined by a third pilot, who many sources name as Geoffrey Stephenson, though there is some doubt.

Bad Show

After lunch some of the civilian pilots pressed them to put on a display and, when they left, they planned to carry out a manoeuvre called the Prince of Wales’ Feathers where the three aircraft climb and then, while the centre one continues the other two peel off to either side. After doing this Bader unexpectedly headed back to the airfield and carried out a slow roll to the right at low level, probably less than 20 feet above the airfield.

When he was three-quarters of the way through the manoeuvre his port wingtip struck the ground and he cart-wheeled to a crunching halt; the propeller and engine were torn off, the left wing buckled and twisted under the fuselage, the lower right wing collapsed and the top wing was torn off. In the crash he severely damaged both legs, a metal bar having gone completely through one knee. He was only saved from bleeding to death by the first aid skills of one of the civilian pilots named Jim Cruttenden.

A few hours later surgeons amputated his right leg and, some days later, his left leg, too. The shock to his system almost killed him but not quite. He was fit and fought back.

Eventually, he was fitted with artificial legs made of aluminium, which, compared to today’s prosthetic limbs, were very, very crude. He was told that he would never walk again, not without a stick at any rate.

“I’ll never, never walk with one,” was his reply.

He was determined, “to go it alone and not be a bore to other people.” Whether he managed that entirely is a moot point but he did learn to walk, and in record time, too. By the time that he left the Royal Berkshire Hospital in February 1932 he told those who came to say goodbye, “I know I’ll be able to fly still.”

The Air Ministry did not share this belief and posted him to RAF Duxford as Officer in Charge of the Motor Transport Section. The MT Section from that time is still here, buildings 73 and 74 and, though they’re not currently in an area open to the public, they can be seen behind Number 3 Hangar, the Air and Sea exhibit.

Retirement

Despite the fact that he, unofficially, flew while he was here at Duxford and was as much of a natural without legs as he had been with, it was clear that he would not be allowed to continue as a pilot in the Royal Air Force. Douglas was sent to the Central Flying School and found his abilities as a pilot had not been impaired by the loss of his legs. He passed all the flying tests but the medical officer refused to pass him as fit to fly as there was “nothing in regulations” to cover his case.

Soon he received a letter from the Air Ministry, via the acting Station Commander at Duxford, stating that he could no longer serve in the General Duties branch of the RAF – the branch to which pilots belong – and suggesting that he should retire. He left the RAF, exiting through the main gates at Duxford, on 30th April 1933.

Imagine for a second, he was 23 years old; his hopes of playing cricket and rugby for England – both of which were realistic - in fact, he had already been selected for the England rugby squad prior to his accident - were now dashed. His dream of a career as a fighter pilot had gone; destroyed in an accident which he knew was down to his own misjudgement. An accident which had left him – even though he would never admit it – severely disabled. How must he have felt at that point?

Consider also how different it would be for him today, sadly the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan have made limbless servicemen too common a thing but the advances in prosthetic limbs have been amazing. He could have stayed in the service, he could have been a star of the Invictus Games or a gold medallist at the Paralympics. But, in 1933, that was not the way things were, Bader left the air force, seemingly for good.

However, Douglas Bader being Douglas Bader, never stopped petitioning the Air Ministry for a way back. By the time of the Munich Crisis in September 1938 he had been offered a commission in the administrative branch which he had declined. By the spring of the following year he had managed to get Air Marshal Sir Charles Portal to agree that if war broke out the Air Ministry would “almost certainly” allow him to fly if the doctors would; Portal’s staff officer at the time was a man called Geoffrey Stephenson.

War

Of course, in September 1939, war with Germany was declared.

Air Vice Marshal Halahan, who had been commandant at Cranwell during Bader’s first year there, allowed him the opportunity of attending the Central Flying School for an assessment and on 18th October he reported to RAF Upavon. A month later he was re-instated on flying duties in the rank of Flying Officer.

At 3.30 PM on 27th November 1939 he soloed in the Avro Tutor K3242 after just 25 minutes and completed his refresher training in January 1940.

It was, however, still by no means certain that he would be allowed to fly operationally on fighters but he enlisted the help of his old friend Geoffrey Stephenson who by now was commanding 19 Squadron based at Duxford.

Bader borrowed a Central Flying School Hurricane – as you do - and flew into Duxford on the day that the Air Officer Commanding No. 12 Fighter Group, Air Vice Marshal Trafford Leigh-Mallory, was visiting.

Sqn Ldr Woodhall, at that time in charge of flying operations here, introduced them and over lunch Bader set to work persuading Leigh-Mallory that he should return to operational flying. Afterwards he flew an aerobatic display over Duxford in the Hurricane, observed by the AOC.

On 7th February 1940 he was posted to 19 Squadron at Duxford returning to operational service in the RAF through the same gates he’d left behind almost seven years earlier. He first flew a Spitfire (K9853) five days later and his first operational sorties came a few days later.

His commanding officer was his old friend from Cranwell and Kenley, Geoffrey Stephenson.

Promotion

In April Bader 1940 was promoted to Flight Lieutenant and posted to 222 Sqn, also based at Duxford and also flying Spitfires, as a Flight Commander.

He claimed his first “kill” – shooting down an enemy aircraft – on 1st June 1940. As a matter of fact, he claimed five kills but was only credited with one Me109 shot down and one Me110 damaged – which was probably much closer to the truth. This wasn’t unusual in the heat of battle.

In June 1940 Bader was posted to Coltishall in Norfolk as an acting Squadron Leader, commanding 242 (Canadian) Squadron flying Hurricanes. As Edward Sims said in his book, The Fighter Pilots “When some of the Canadian pilots heard the news about his incapacity, they assumed he would do little flying and prove to be a somewhat inactive leader. It was one of the worst guesses of the war.”

Bader had, in just seven months, caught up with the rank of most of those he was at Cranwell with.

By now he was certain of the three principles of dogfighting, which had been espoused by the fighter pilots of the Great War:

He who has the height controls the battle

He who has the sun achieves surprise

He who goes in close, shoots them down

By 24th June 1940, he declared the squadron operational but without adequate spares, by 9th July they were fully operational. The Battle of Britain officially commenced the next day.

Battle of Britain

The RAF at this time was split into commands and the one which had the fighter aircraft was, unsurprisingly, called Fighter Command and Air Chief Marshal Sir Hugh Dowding was its Air Officer Commanding-in-Chief.

Fighter Command was then split into Groups covering geographical areas. 12 Group covered the Midlands, Norfolk and Cambridgeshire – which, of course, included Duxford. 11 Group covered the south and east coasts of England.

On Friday 30th August, 11 Group squadrons were all busy and their AOC, Air Vice Marshal Keith Park, asked for a 12 Group squadron to protect North Weald in Essex whilst its fighters were off engaging the enemy. Though still nominally stationed at Coltishall, Bader and his squadron had moved to Duxford – the most southerly station in 12 Group. At 1623 ‘Woody’ Woodhall, who was now the Station Commander and Sector Controller scrambled the 14 Hurricanes of 242 Squadron from the Operations Room at Duxford. The Sector Controller was responsible for getting the aircraft to within sight of the enemy – at which point the fighter leader took over.

He instructed 242 to patrol over North Weald at 15,000 ft as the enemy had a force of 70 plus bombers heading that way. When the main formation of bombers was spotted Bader was above them with the sun behind him. There have been suggestions that he climbed higher and patrolled some 20 miles away to put himself in this position but his own combat reports do not reflect this.

In the battle which followed the squadron, under Bader’s leadership, claimed 10 enemy aircraft destroyed, 2 probables and 2 damaged – no Hurricanes were lost on that day and no bombs fell on North Weald. When Leigh-Mallory came to congratulate the squadron, Bader made it clear that if he’d had more aeroplanes, they’d have done even better.

Soon afterwards, what became known as the Duxford Wing was formed and, on 7th September 1940, the day on which the German tactics changed focus, from attacking RAF airfields to bombing London, specifically with the aim of getting as many RAF squadrons as possible in the air, Bader led a wing of three squadrons from Duxford – 242, 19 and 310. This seemed to vindicate the idea of the Wing as 20 enemy aircraft were claimed as destroyed. Two days later the Wing flew again and claimed 21 destroyed.

Two more squadrons – 611 and 74, which was later replaced by 302, were added to the Duxford Wing; this became known as the Big Wing.

On the 15th September 1940 – what was to become known as Battle of Britain Day, a day which is still commemorated – the Luftwaffe launched a series of raids on London. The early mist had cleared to leave a fine day when, at 1130, the Duxford Big Wing was scrambled to patrol between Canterbury and Gravesend. Three Hurricane squadrons at 25,000’ and two Spitfire squadrons 2,000’ above them – all led by Bader.

They engaged a formation of Dornier bombers and their Me109 escorts and claimed a total of 26 enemy aircraft destroyed. They were scrambled again at 1430 and claimed another 26; the wing lost 2 of their 56 pilots that day.

The reason this is known as Battle of Britain Day is not simply the scale of the German losses – which had been higher on two days in August (15th – Black Thursday and 18th – The Hardest Day) – it was the fact that the Luftwaffe had been told by Goering that they should expect to destroy the last 50 Spitfires in the RAF, instead they were met by large forces, this led Hitler to abandon his plans for the invasion of Britain.

Argument

The Big Wing seemed to be a success but it was not without its critics. Not least Air Chief Marshal Sir Hugh Dowding, AOC-in-C of Fighter Command and the head of 11 Group, Air Vice Marshal Keith Park. I believe that they had no quarrel with the idea of wings – in fact Park had used them in offensive operations over Dunkirk and, when conditions allowed, throughout the Battle of Britain – they just didn’t agree with using them routinely, in the current defensive situation.

There is no doubt that there were arguments both for and against the Big Wing. There were those, particularly within 11 Group, who argued that the Big Wing took too long to form up. Set against that, Bader argued that 11 Group did not pass the information on in time, though this was possibly a misunderstanding about just how capable the radar and communication systems were. The truth was, though, that, due simply to geography, 11 Group and 12 Group were fighting two different battles. AVM Sir Douglas Evill, Dowding’s SASO, summed it up when he said, “It is quite useless to argue whether Wing formations are or are not desirable, both statements are equally true under different conditions.” Something with which Bader himself agreed.

Dowding and Park, unlike Bader and Leigh-Mallory, were also aware, from their access to Top Secret intercepted and decoded German communications, that a Nazi strategy – specifically on 7th September when invasion was believed to be imminent by both sides - was to get as many RAF aircraft in the air as possible.

Hermann Goering, the head of Germany’s Luftwaffe, considered this to be key to defeating the RAF and gaining air superiority to enable Hitler’s plans for the invasion of Britain to go ahead.

This knowledge may, to some degree, account for Dowding and Park’s dislike of the Big Wing tactics and the secrecy surrounding how they knew that may account for the fact that they never seem to have articulated their criticisms quite clearly enough.

Bader was invited to a meeting in London on 17th October to discuss major day tactics in the fighter force. Keith Park said that he felt that the current 11 Group tactics were best at defending against the raids. Leigh-Mallory said that he would welcome more opportunities to use the Duxford Wing and Bader put forward the view that if enough warning could be given there was no doubt they could get the most effective results with a wing.

Sholto Douglas, in his role as Deputy Chief of the Air Staff, felt that both tactics had merit, depending on the situation. Hugh Dowding conceded that it would be arranged for No. 12 Group wings to participate in suitable operations and that he could resolve complications of control.

The arguments about the Big Wing carried on for many months. The Under Secretary of State for Air, Harold Balfour, visited Duxford on the 2nd of November, specifically to report on this topic at Churchill’s request. In what became known as the Duxford Memorandum, he came down in favour of the Big Wings, for which Dowding strongly criticised him. Dowding was soon replaced at Fighter Command by an advocate of the Big Wing, the newly promoted Air Marshal William Sholto Douglas.

By December offensive sweeps over France had started and nobody ever doubted the use of wings as an offensive tactic.

Leigh-Mallory replaced Park as head of 11 Group - Bader and 242 Squadron followed him, moving to Martlesham Heath in Suffolk.

9th August 1941

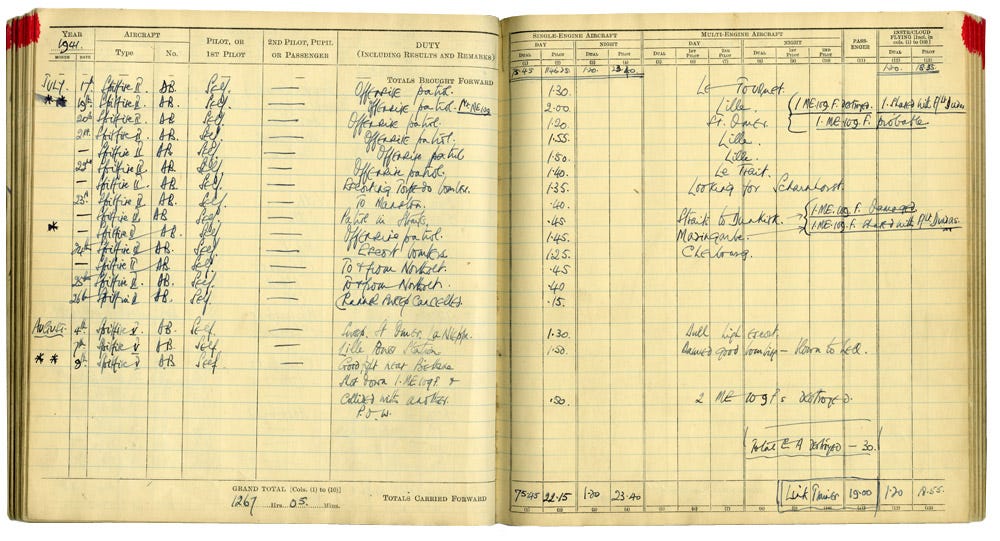

Bader went on to be a Wing Commander at Tangmere and on the 9th August 1941 he led the Wing on a mission known as Circus 68 in support of Blenheims bombing a power station at Gosnay. He took off at 1038 from Westhampnett, with Sgt Jeff West flying as his Number Two, leading 616, 610 and 41 squadrons.

No. 11 Group’s Operational Order No. 75 – Circus 68 – Attack on the power station at Gosnay by five Blenheims of No. 2 Group, each carrying four 250lb bombs. These aircraft from 226 Squadron, which was based at Wattisham, operated from Manston on the day where they rendezvoused with their escorts at 1100 at 10,000 feet.

No. 11 Group provided an escort wing from North Weald comprising 111, 222 and 71 squadrons led by Wg Cdr John Gillan; an escort cover wing from Hornchurch, made up of 403, 603 and 611 squadrons and led by Wg Cdr Stapleton; and two target support wings: 452, 602 and 485 squadrons of the Kenley wing, whose leader Wg Cdr Kent did notfly on Circus 68; and the Tangmere wing, 41 Sqn flying out of Merston and 610 and 616 squadrons, taking off from Westhampnett with Bader leading at 1038. Bader’s callsign was Dogsbody, his section was made up of Sgt. Jeff West (Dogsbody 2), Fl. Lt. Hugh Dundas (Dogsbody 3) and Plt. Off. “Johnnie” Johnson (Dogsbody 4).

Bader’s ASI was unserviceable and so he instructed Flt Lt Hugh “Cocky” Dundas to take the lead until they reached the target area. At 1112 Flt. Lt. Roy Marples spotted the enemy. A dogfight ensued.

The last transmission from Bader was at 1123 when, in the middle of the dogfight over France, he called to someone, probably Jeff West, “Stay with me.” Soon after that, Bader was shot down – the Germans said he was shot down by an NCO pilot, an idea which Bader found “intolerable” but one I rather like. Certainly by 1130 calls to Bader were not being answered.

The bombers arrived in the area of their target at around 1125 but cloud cover meant that Gosnay could not be found. They endeavoured to find their secondary target but that too was obscured. Eight bombs were dropped harmlessly in a field near Fort Phillipe, the other twelve were dropped in the sea.

Bader at first accepted that he had indeed been shot down but, pretty soon, seemed to be of the opinion that he had collided with an Me109 and lost the tail section of his aircraft. He was trapped by his right leg for some time, eventually managing to bail out at about 6000ft.

Given the confirmed German losses on that day, this seems unlikely. If he did collide it was not with a German aircraft. It is far more likely, though, that he was shot down. The best German candidates for this were, indeed, NCOs: Oberfeldwebel Walter Meyer who reported that he shot down a Spitfire near to St Omer between 1125 and 1130 and Oberfeldwebel Erwin Busch who also reported that he shot down a Spitfire at 1125; both were pilots of Adolf Galland’s Jagdgeschwader 26. Oberleutenant Johannes Schmid was later introduced to Bader as the man who shot him down, evidence suggests that the Spitfire Schmid shot down that day was actually that of Sgt. Gerald “Barry” Haydon.

Shot Down?

It is very likely that, in the confusion of battle, he was shot down by one of his own Spitfires; a conclusion which, I believe, he may have come to himself, hence the story about the collision taking root to protect the British pilot involved.

11 Group claimed to have destroyed 13 Me109s with 7 probables and 6 damaged. The only loss from JG26 during Circus 68 was of 20-year-old Unteroffizier Albert Schlager. This was the only enemy aircraft actually shot down during the operation and the wreckage has been found – with the tail unit intact.

Flt. Lt. “Buck” Casson claimed to have shot down a lone Me109 which lost most of its tail unit, the pilot finally bailing out at around 6000ft.

Whatever the truth, Bader spent the rest of the war as a prisoner, ending up at the infamous Colditz castle after numerous escape attempts. After the war he returned to England and was promoted to Group Captain, leading the very first Battle of Britain Day flypast over London in September 1945.

He left the RAF in 1946 and spent the rest of his life working for Shell and raising awareness about disability and a great deal of money for charities which supported the disabled, for which he was knighted in 1976. I think he would have been very pleased about how attitudes and opportunities have changed over the last eighty-five years.

What isn’t quite as well known is that Douglas Bader wasn’t the only legless pilot in World War Two. There was a Russian fighter ace called Aleksey Petrovich Maresyev who had lost both legs in 1942 and returned to flying the following year.

In fact, Bader wasn’t the only legless RAF fighter pilot to fly Spitfires from Tangmere and crash close to St. Omer during World War Two. There was one other: Colin “Hoppy” Hodgkinson.

Another Duxford Story

Here’s another very short story about someone I mentioned earlier; someone in whose life Duxford, Bader and 26th May played a big part.

On 26th May 1940 Squadron Leader Geoffrey Stephenson, as CO of 19 Squadron, was flying his Spitfire, registration N3200 on its first operational mission. He was leading eleven other Spitfires on a sortie to help cover the evacuation of troops from the beaches at Dunkirk. Stephenson was shot down by a Ju87. After evading capture for eight days and walking the two hundred kilometres to Evere on the outskirts of Brussels, he handed himself in to the Luftwaffe and spent the rest of the war as a prisoner.

His Spitfire lay in the mud on the beach at Sangatte until 1986 when it was rescued. It was restored to flying condition at Duxford in 2014. You may have seen the story of the restoration as told by Guy Martin on Channel 4. N3200 was given to the IWM as a gift by its owners and can still be seen at Duxford today.

Sources

Brickhill, P. (1954). Reach for the Sky. London: Collins.

Burns, M. (1998). Bader - The Man and His Men. London: Cassell.

Hodgkinson, C. (1957). Best Foot Forward. London: Odhams Press Limited.

IWM. (2015). The Spitfire Lost for Almost 50 Years. http://www.iwm.org.uk/ , http://www.iwm.org.uk/history/the-spitfire-lost-for-almost-50-years. Retrieved 11th May 2025

Jackson, R. (1983). Douglas Bader A Biography. London: Arthur Barker Ltd.

Lucas, P. (1983). Flying Colours. St. Albans: Granada Publishing Limited.

M&AFD 1/111/HF. (21 March 1932). Colonel I/C Military and Air Force Department, JAG's Office, to AOC Fighting Area . Kew: National Archives.

Mackenzie, S.P. (2010). Bader's War. Stroud: Spellmount Publishers.

Minutes. (1940). Minutes of a meeting held in the Air Council room on 17 October 1940 to discuss major day tactics in the fighter force.

RAF Museum. (2020). Douglas Bader – A fighter pilot again https://www.rafmuseum.org.uk/research/online-exhibitions/douglas-bader-fighter-pilot/a-fighter-pilot-again/ Retrieved 4th May 2025

Sarkar, D. (2006). Bader's Duxford Fighters. Worcester: Victory Books International.

Sarkar, D. (2021). Bader’s Big Wing Controversy. Barnsley: Pen & Sword Books Ltd.

Sarkar, D. (2022). Bader’s Spitfire Wing. Barnsley: Pen & Sword Books Ltd.

Saunders, A. (2017). Bader's Last Fight. Barnsley: Frontline Books.

Shields, J. (2024). Spitfire Pilot Air Commodore Geoffrey Stephenson. Barnsley: Pen & Sword Books Ltd.

Sims, E. (1967). The Fighter Pilots. London : Cassell.

St. Edward’s School. (2017) Commemorating Douglas R. S. Bader https://www.stedwardsoxford.org/2017/09/06/commemorating-douglas-r-s-bader-o-s-e/ Retrieved 4th May 2025

Turner, J.F. (1981). The Bader Wing. Tunbridge Wells: Midas Books.

Turner, J.F. (1986). The Bader Tapes. Bourne End: The Kensal Press.

Turner, J.F. (2021). Douglas Bader. Barnsley: Pen & Sword Books Ltd.

TV. (1982). This Is Your Life. London: Thames TV.

Wikipedia. (2025). https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Aleksey_Maresyev Retrieved 11th May 2025