“For they were young and the Thames was old,

And this is the tale that the river told”

- Rudyard KiplingDocklands is the name now given to the area that was, for years, the heart of the Port of London. The blocks of council houses and flats spread north of Victoria Dock Road in the area known as Custom House. They must have been built as the docks declined. I walked past the houses and tried not to imagine living here. The unfeasibly popular cockney actor and descendent of Edward III, Danny Dyer, grew up in this area and I’m sure that thousands of people have lived happy lives here, it’s just it wouldn’t be the place for me. I may have been born in a city but I’m a country mouse at heart.

In his book, Notes from the Green Man, Chuck Dalldorf tells a story of an old Suffolk boy who says that he went to London once but didn’t see the point. I can understand that. No more do I believe Johnson’s assertion that a man who is tired of London is tired of life. Anyone who is tired of London might just have a point, I guess it’s handy for the shops, though.

I crossed a footbridge and negotiated my way past some building sites before arriving at the water’s edge and the Emirates Air-line where you can use your Oyster Card to cross the river on a cable car. That blew my mind but, there again, perhaps I just don’t get out much.

I shared a car with an American couple who asked me what the Millennium Dome had been built for. I had to admit that I didn’t know but feared that if it hadn’t been for the odd war it might have been the Blair government’s biggest crime. The dome is the biggest construction of its type anywhere. You have to ask yourself why that is, why no-one else has done it.

My American companions guessed that the yellow support towers sticking up out of it represented all of the cranes that we could see right across London from our cable car. They weren’t correct, the twelve supports represent the twelve hours on a clock face representing the role played by Greenwich in the world’s time-keeping. There’s no point doing stuff like that, though, if I have to look at Wikipedia to find out and all the world’s tourists think you’re taking the mickey out of the fact that London will never be finished.

I’d never visited the Millennium Dome while it was the Millennium Dome and I’d never previously visited it as the O2 Arena, either. As I said, I don’t get out much. The O2 was, apparently, the world’s busiest arena in 2017, so perhaps I was missing something special. I have to say, if I was, then I missed it again today.

In most towns and cities in Britain you will find a large car park next to a multiplex cinema, which is surrounded by some chain restaurants. If you imagine that all of these places in Britain joined the Scouts and went camping, then you’d know what the O2 Arena was like. In fairness, I only walked around the periphery, not being allowed into the main arena. However, I can’t see me coming back.

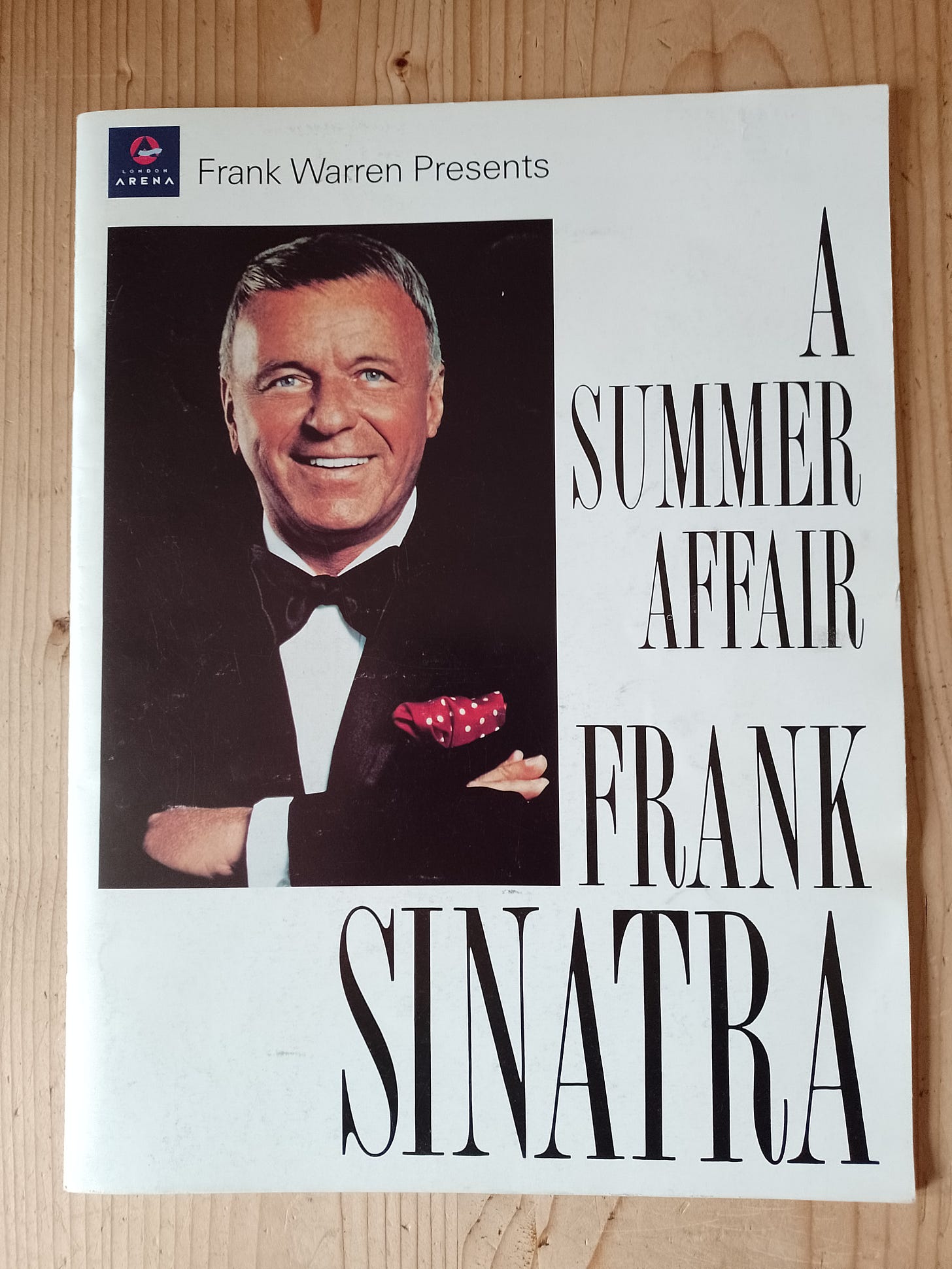

I do like Docklands, though. I had first visited the area on the evening of 4th July 1990, the night of the World Cup semi-final between England and West Germany, the night that my mate Dave had the idea of popping to London to see Sinatra in concert at the London Arena. We had quite a distance to just “pop”, but I’ll tell you more about that some other time.

The London Docklands Arena was part of the redevelopment of the area and was built on the site of the Fred Olsen banana and tomato warehouse at the old Millwall Dock. It opened in 1989 and hosted sports events, trade exhibitions and concerts. It had started to lose money way before it opened and carried on in much the same vein until the day it closed in 2005. Perhaps the oddest part of its life was as the home of the London Knights, an ice hockey team who were then part of the British Ice Hockey Super League.

The main problem with the British Ice Hockey Super League was that not enough British people gave a flying monkey’s muff about ice hockey. The league, and many of the teams that had played in it, had disappeared by 2003. Some of the teams still exist, though: the Sheffield Steelers; the Nottingham Panthers; the Cardiff Devils; the Bracknell Bees; the Belfast Giants; and the weirdly named Basingstoke Bison are all going strong. This tells you a lot, probably all you ever need to know, about living in Sheffield, Nottingham, Cardiff, Bracknell, Belfast or Basingstoke.

Another problem with the Docklands Arena was transport, while it was well served by the Crossharbour and London Arena station of the Docklands Light Railway, you couldn’t drive there and park, there being about twenty-seven parking places for a fifteen-thousand-seater arena. Of course, when the Millwall Dock was originally developed, arriving by car was not due to be an option for twenty-four years as it opened in March 1868 - the first four-wheeled petrol-driven automobile in Britain was built in Walthamstow by Frederick Bremer in 1892. Timber and grain were, originally, the main commodities landed here but, by the 1960s, trade was beginning to disappear and the docks finally closed in 1981.

Walking round a lot of the Docklands today, it looks like the establishing shots from the early Star Trek movies where they’re showing you life on earth in the twenty-third century. Great glass buildings rise around you, there are shapes of buildings and materials used in their creation, that you’ve never seen before. Covered walkways criss-cross overhead and driverless trains flash by high above you. Huge shapes made of curving sheets of glass, like parts of an armour-plated sea monster breaking the surface, loom up out of the polished pavement. The shops are underground, shining marble and artificial light under manicured parks where little footbridges let you look down through skylights into the malls below. There are fountains and sculptures and bright flower beds. Apart from the general reticence of the inhabitants to wear tight-fitting jumpsuits, you could be forgiven for expecting to see Spock and Bones appear from around the next corner.

Canary Wharf is set about three miles to the east and about a century into the future of the centre of London. Groups of well-dressed and well-groomed young people move around looking like the cast of Logan’s Run have just nipped out for a fag. I did see a lot of people smoking here, especially in the areas marked “This is a No Smoking Area”. There were far more smokers than you see in most other places these days. Perhaps it’s due to the stress of the jobs they have or maybe smoking is safe in the future.

There’s lots of everything here, though. Restaurants and cafes, for instance. You could live your whole life here and not get round to eating in all of them. I walked over the top of more shops in half an hour than there are within a thirty-mile radius of my house. I live in a village which doesn’t even have a shop; but here, Moleskine have a whole shop just for their notebooks and stuff. I have to cycle for fifteen minutes just for a pint of milk.

Then you cross the water and step back in time, far further back than where you remember starting out. It’s like Picard on the holodeck; you’ve arrived at the Museum of London Docklands. This is a fantastic museum and I don’t say that simply because entry is free, I would have paid the five pounds suggested donation if I’d had any cash on me, really I would. It really is great. So many stories, skilfully told: reconstructions, films, dark streets, warehouses, models, maps and artefacts. The history of the docks here comes to life, you can almost see the masts of the tall ships and rowing boats with barrels of brandy. The museum is housed in what were warehouses on the West India Import Dock which opened for business in 1802. The driving force behind the construction of the docks was a plantation owner called Robert Milligan. He was also largely responsible for an Act of Parliament which then made it law that all imports arriving in London from the West Indies must pass through this dock. This remained law for twenty-one years, well past the death of Robert Milligan and up until the beginning of the end of the slave trade which had fed the imports from the West Indies.

In 1823, Thomas Fowell Buxton MP made a speech in the House of Commons in which he pointed out the ludicrous circular argument which allowed people to believe that slavery was in some way defensible: “We make the man worthless, and, because he is worthless, we retain him as a slave. We make him a brute, and then allege his brutality, the valid reason for withholding his rights.” Even though the slave trade itself had been abolished in Britain in 1807, slavery still supported much of the trade arriving from other parts of the world, including the pink-shaded parts run by Britain. Fowell Buxton said that slavery was "repugnant to the principles of the British constitution" and called for its abolition "throughout the British colonies". Most of the rest of his parliamentary career and his life were devoted to this cause. The museum brought those years to life for me.

Next week, for my paid subscribers, I’ll look at how Docklands came to be what it is today. Paid subscriptions enable me to carry on writing Bunking Off and give you access to around twice as many posts and the entire archive of posts. For everybody else, we’ll pop up to Newcastle in a fortnight’s time. Thanks for reading.

Fascinating stuff! You were sitting at the other end of the table at the East Anglian Writers session today. I didn’t get a chance to catch up with you to talk about flying. Not something I do, but my son is a captain with EasyJet, so I keep an eye on these things!